It was glorious. Jaw-dropping, even.

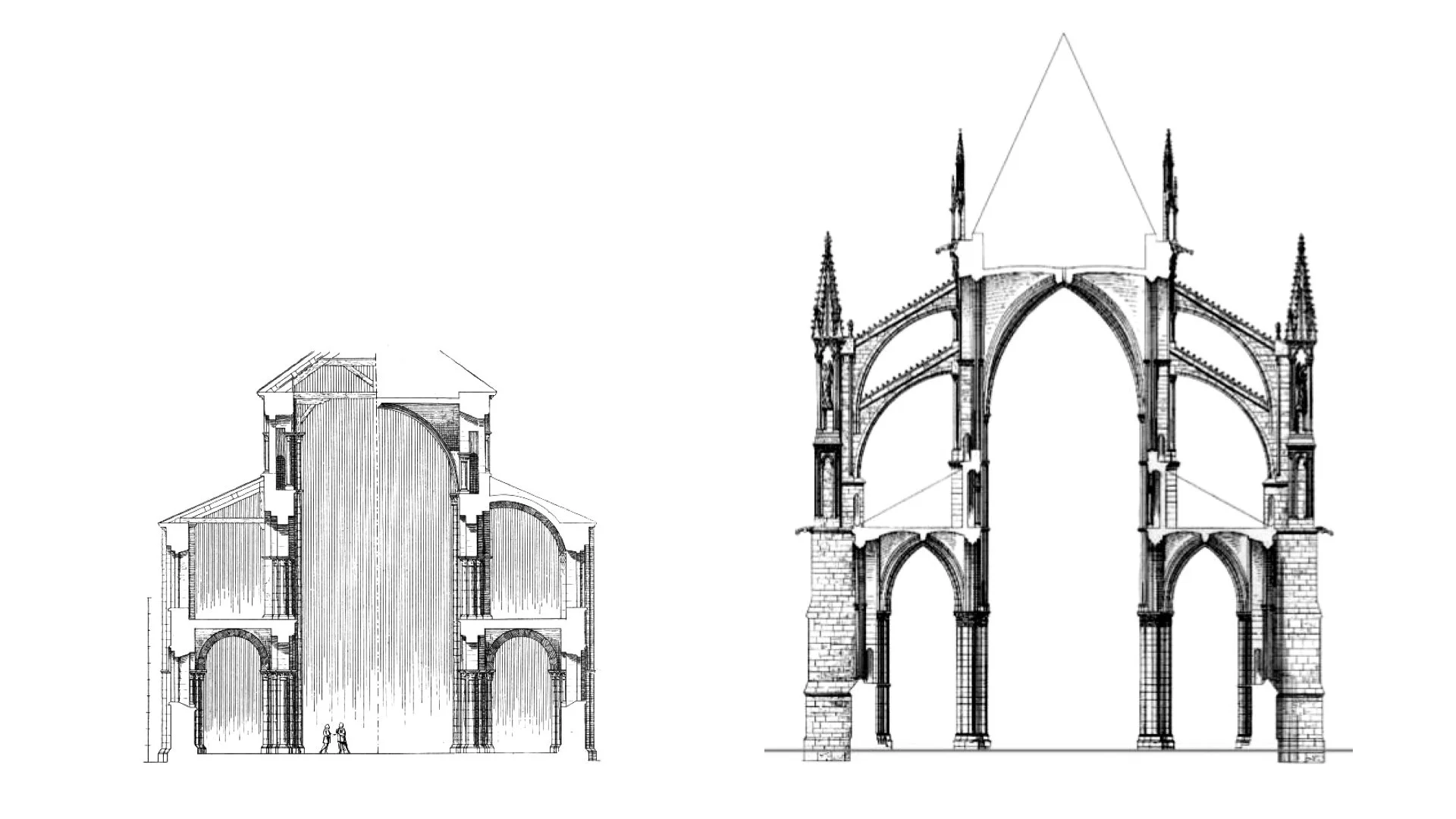

European engineers of the late 12th and 13th centuries flipped the paradigm. They took the bulkiness of the Romanesque and stretched it tensile thin. The resulting structures could no longer be converted into a stronghold; that was earth-bound thinking. No, new lines defied gravity and carried the faithful to a place that was, by design, unearthly, buoyant, positive.

The focus shifted from divine security to divine glory.

A comparison (sorta-kinda to scale) between two grand examples. The first (left) section is a Romanesque-style structure, the Abbey of Saint-Étienne in Caen, France. Construction here was initiated in the 11th century. The second (right) section is a Gothic-style structure, the Reims Cathedral in Reims, France. Construction here was initiated in the 13th century. Notice how “flying buttresses,” like flanking bridges above the roofline, help transfer the weight of the taller building on the right from its midpoint to its edges. While ideas of weight and balance were not new, they were expanded and developed in fresh ways within the Gothic movement. Find the first image here, the second image here (both accessed 1/26/2022).

Of course, paradigm shifts don’t happen overnight, especially in a field that moves with the speed of sedimentary rock. Designers did not live long enough to see their visions through. Generations of individuals and centuries of experimentation were required. Failures must have been many; deadly collapses, unnumbered. Stacked-stone walls, after all, do not stretch so easily! But examples have survived to our own day—still reaching heavenward after almost a thousand years of time. These demonstrate the brilliance of this architectural yearning originally dubbed “French Work” (Opus Francigenum) by its contemporaries.* Gothic was born.**

(Side note: I find it ironic that in our own day the term gothic is often used of things dark and deathly. Consider the quivering line of literature that stretches from Ed Poe to Steve King, or, the more fashionable goths on the street, forever on the hunt for that elusive Victorian funeral. Mystery does play a role in gothic architecture, but its character is anything but morbid. It is ebullient.)

I shot this image of the Cathedral of Saint Mary of Burgos at first light. Remove the spires in your imagination (they were a late addition after all!) and note how similar this façade is to that of its celebrated cousin, the cathedral church of Notre-Dame.*** The hammers in Burgos would have been heard at the same time as the hammers in Paris.

Bob and I walked across Spain, in part, to experience its cathedrals. The Santa Iglesia Basílica Catedral Metropolitana de Santa María de Burgos (or more simply, the Cathedral of Saint Mary of Burgos) did not disappoint. It was glorious. Jaw-dropping even.

Not since leaving France had we seen anything like it (see here for a description of our arrival in Bayonne, or here, for our arrival in Burgos.). The Catedral rose vertically three stories from the center of the city; its spires and steeples mounted the roof and rose still higher, twining to heaven like knobby Jacobian ladders. Looking down from that 84-meter vantage point, the footprint of the structure took the shape of a Latin cross. It was about the size of a football field and faced east.

We stood in line, purchased our tickets, and received our audioguides (see here for the visitor’s website). We split up to wander the nave, its transept, radiating chapels, and innumerable pieces of art.

Listening to the audioguide. And yes, those are giraffe gaiters. We remain fashionable, even on the trail.

I learned that the structure seen today was built over the remains of an earlier Romanesque structure. Bursts of activity between AD 1221 and 1567 account for the bulk of its construction. Because of this, elements of the full evolution of the Gothic style are captured: Early, High (or Rayonnant), and Late (or Flamboyant).

On left, stairs lead up to the Puerta del Sarmental on the south end of the transept. Note the circular rose window high above the doors. On right, the footprint of the cathedral resembles a Latin cross surrounded by smallish chapels. I colored the nave purple and the intercepting transept blue. The choir is in brown. The image of the ground plan was taken from here (and accessed 1/24/2022).

Early Gothic

The Puerta del Sarmental (see the grey arrow on the plan above) is an example of Early Gothic in the Burgos cathedral.

Work on this southern portal began in the year 1230, the same year in which the building witnessed its first mass. The portal was not meant to be the main entrance to the Catedral (that was on the west), although it functions that way today. Originally this was the private entrance used by the bishop and his canons. The figure of a bishop stands on the mullion (or column) dividing the twin doors of the gate. It is possible that this figure represents Bishop Maurico, who studied in France and lobbied for the construction of the Burgos Catedral in this new style. The economic power of Burgos and its important role along the Camino Francés undoubtedly helped his cause.

The decorated arch, or tympanum, over the twin doors is a Romanesque idea, executed in Gothic style. Specialists believe it to be the earliest bit of Gothic on the peninsula, carved by unknown artists trained in France.

Detail of the tympanum above the south portal. It features a “majestic Christ” or Pantocrator holding an open book. He is surrounded by symbols of the four evangelists. Angels and archangels and apostles telescope out from there. Note the figure of the bishop standing between the doors.

High Gothic

If the first phase of the Gothic movement emphasized increased size, the second filled that expanse with decoration and light. This elegant weightlessness is dubbed rayonnant, or “radiant" in France, or “decorated” in England. It marks the high point of the movement and is usually referenced by means of stained-glass windows.

Flat walls with small windows were replaced by sheets of transaparency. Mosaics of dazzling color infused the white stone with life. Biblical scenes and great saints danced overhead.

Burgos became a center of glass production. Workshops here produced glass for not only this new Catedral, but for projects elsewhere as well. The deep red glass of Burgos was legendary.

The lone survivor of the blast of 1813: the Rose Window of the Puerta del Sarmental. Image from here (accessed 1/27/2022).

Unfortunately, the Burgos Catedral lost almost all its original glass when retreating French soldiers blew up the nearby Castille as part of the Peninsular War in 1813. The city absorbed the blast; the noise was heard 50 miles away. Glass shards and stone tracery flew everywhere. All but the rose window of the Puerta del Sarmental (dated to 1260) were destroyed.

Consequently, the best example of “pure” style rayonnant in Spain is in León (stay tuned, we’ll get there in a later post). In Burgos, apart from the rose window, this second phase Gothic is best identified in the remains of its cloister tracery and sculptures (I colored the cloister yellow in the plan above).

This image, captured by Gerhard Huber, offers a view to one cloister hall. Note the rows of vegetal ornaments decorating the arches on the left. Image from here (accessed 1/28/2022). This realistic (and exuberant) decor has been linked to the style rayonnant in Spain.

Late Gothic

The third and final phase of the Gothic movement is dubbed Late (or Flamboyant in France, “Perpendicular” in England). The name flamboyant is derived from the flame-like or curvy lines found in window tracery, ribs, balustrades, and other ornaments.

As a single example, note the curving rib vaulting that supports the roof on all four sides of the intersection of the center nave and transept. Viewed from below, the “lantern tower” (such features rise above the roof and let in light) is breathtaking. It also underlines all three aspects of the Gothic experience: expansive space, bright illumination, and curvy ornamentation (You can find the lantern tower of the Burgos Catedral marked on the plan above by the white square).

Flamboyant rib vaulting supports the roof around the lantern tower.

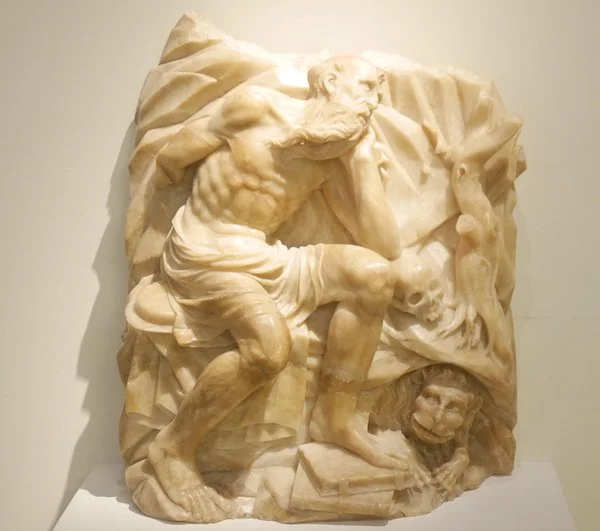

Bob and I saw and learned many things on the day we visited this cathedral. Its stunning architecture was only the beginning. We stood beside the grave of El Cid, a folk hero of Spain. We saw a painting of Mary Magdalene, believed by many to be the work of Leonardo da Vinci. We marveled at an alabaster carving of old St Jerome, the translator of the Latin Vulgate. In the end, the site exceeded our own energy.

Truly, it was glorious. Jaw-dropping, even.

¡Buen Camino!

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of Burgos exceeded our energy. Bob took a rest with a tired pilgrim at the Plaza Rey San Fernando.

*See here for more on use of the phrase “French Work” (accessed 1/26/2022).

**It is believed that Renaissance artists and writers in the 16th century coined the label “Gothic.” It was originally used as an insult, descriptive of the kind of work a barbarian (or Goth) would produce. But in all fairness, by the 16th century, the artistic style had passed its heyday and was in decline. For more, see here (accessed 1/26/2022).

***Victor Hugo, the author of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, visited the cathedral of Burgos as a child. It is claimed that the building in his novel more closely resembles the cathedral in Burgos than the cathedral in Paris! See the link here (accessed 1/25/2022).

Bob and I walked the Camino Francés in the summer of 2018. The stories posted here were reconstructed from my notes, photographs, and memories.