is not Papa. But he did leave us with an interesting riddle.

"Kilimanjaro is a snow-covered mountain 19,710 feet high, and is said to be the highest mountain in Africa. Its western summit is called the Masai 'Ngaje Ngai,' the House of God. Close to the western summit there is the dried and frozen carcass of a leopard. No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude" (Source here).

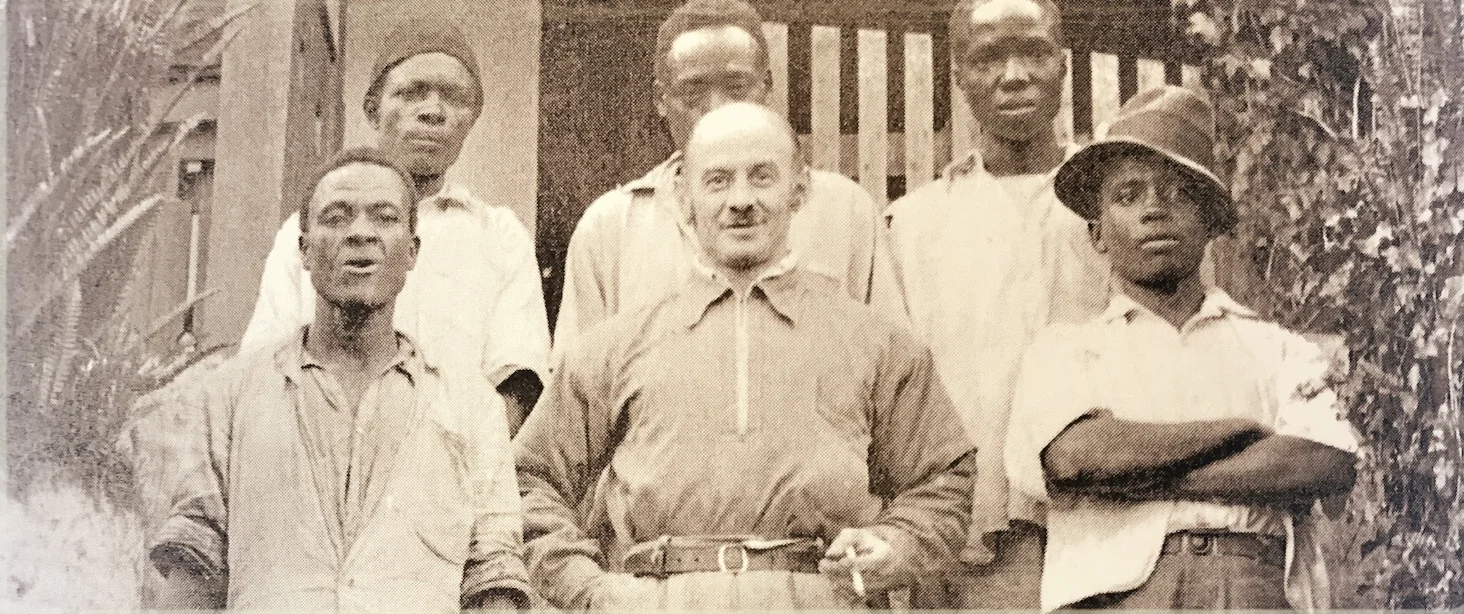

Papa in the field, 1939. Image from here.

Ernest Hemingway dangled this riddle of death at the front end of his short story, "The Snows of Kilimanjaro." The relationship between the leopard and the experience of Harry, the sullen protagonist, is up for debate (see Jerianne Wright's view here as example). But what kind of epigraph is this? Is the leopard a fictitious creation of the narrative itself? A freeze-dried window decoration? A chewy historical tidbit? Something else?

Keep in mind that Papa's experience of Kilimanjaro was under and not on the mountain. Assuming some non-fictional seed rests behind the comment, he could not have seen this feline popsicle personally. Fact is, at the time of "The Snows" publication in 1938 very few people could have.*

Among the ranks of the possible is Hans Meyer. The German had been the first European to reach the roof of Africa. In his published notes (1891) he reports finding a dead antelope near the summit.** Hemingway's riddle is an echo of Meyer's marvel: "How the animal came there it is impossible to say." Was Papa reading the German?

A more likely source of the riddle is Richard Gustavovich Reusch (1891-1975). His story is not fiction, although it reads like it. A library run to locate the biography of the man reveals the truth of the claim.*** I am only half-way through it and already Reusch has been added to my short list as one of the most interesting men in the world (see mention of him in our blog here). The details that follow are largely drawn from Johnson's biography of his life.

Richard Reusch (right) with the Henrich Pfitzinger family cross the Suez Canal on their way to Tanganyika Territory. February, 1923. Image from Johnson (2008: 121).

The explorer-missionary-educator began his adult life as a student at Dorpat University in Imperial Russia. His focus was ancient languages, history, and biblical exegesis. He was ordained as a pastor with the Evangelical Lutheran Church and gripped this perspective for life.

After fleeing his homeland during the Bolshevik Revolution he earned advanced degrees in biblical studies. He was offered a professorship in Oriental Languages at Tartu University (Estonia) but refused the offer in order to do missionary work in East Africa. The next thirty years of his life were focused in Tanganyika. There, Dr Reusch and his bride, Elveda, made a home and raised a family. He learned the languages and traditions of the locals, started and directed schools, clothed the poor, fed the hungry, baptized the repentant, entertained the visitors, trained vocational leaders, trekked the bush, shot the lions, and climbed Mt Kilimanjaro, not once, but fifty times! In order to gain a greater understanding of Islam, he traveled widely in Northeast Africa and Southwest Asia. At times, his survival required the disguise of a whirling dervish from the Caucasus!

According to the register, Reusch was the 7th European to climb Kilimanjaro’s Kibo Peak. He returned two more times in 1926. Rather than plant a national flag, he preferred a Christian symbol.

Hemingway collected the material for "The Snows" in the course of his own African travels in 1933. At that moment in time, no European was more familiar with Kilimanjaro's heights than Reusch. By 1935, just two years after Hemingway's visit, Reusch had already summited Kilimanjaro 25 times. The good doctor founded the East African Mountain Club and trained the first generation of Kili guides. His exploits were so locally famous that the Masai nicknamed Reusch "Son of Kibo."

It is in this role as climber that a connection with Papa's leopard may be proposed.

Jonathan, Mikani, and the remains of a frozen leopard on Kilimanjaro, 1926. Image from here.

Following his second ascent of Kibo in 1926, Reusch published a report in The Tanganyikan Times. There, he confessed,

"I found the frozen leopard which on the former trip my guide and I had replaced on top of a rock situated on the rim of the crater" (Johnson 2008:202).

Several scholars linked Hemingway's riddle with Reusch's feline sighting. Years later, John Howell contacted Reusch directly to inquire about the connection. Reusch replied:

"I found the body of the frozen antelope on the tongues of the Ratzel Glacier and the body of the frozen leopard in the middle notch. I put the latter on a piece of rock so that he looked into the crater. A number of climbers saw it there, brought down parts of his body, and the place was called "Leopard Point." Both bodies disappeared in the mean time except for a few bones" (Johnson 2008:202).

A "freeze-dried" leopard found near the 18,500' mark on Kibo. This 1926 photograph may show Elisabeth Wiegand Müller, the first European woman to summit Kilimanjaro, and her guide Richard Reusch. Image from here.

No encounter between Hemingway and Reusch is known. However, Reusch did put the pieces together.

Papa's riddle: "No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude."

Reusch's explanation: The antelope sought the salt flats. The leopard sought the antelope. Both were caught in a sudden snowstorm.

The iconic summit of Kibo, 1938. Reusch Crater forms a perfect circle on the top of the mountain. Image from here.

Epilogue: In 1953 the British governor of Tanganyika named the volcanic mouth of Kibo "Reusch Crater" after the famous "Son of Kibo." A nearby feature was dubbed "Elveda Point" after Mrs. Reusch. These names are found on maps to this day.

Yet another epilogue: In 1971 Reusch returned to the Middle East and climbed Mt Sinai a second time. He was 79 years old.****

*Ernest Hemingway's "The Snows of Kilimanjaro: A Long Story" was first published in Esquire (August, 1936). It has been reprinted in several other venues since that time.

**An English translation of Hans Meyer's report, Across East African Glaciers: An Account of the First Ascent of Kilimanjaro (1891) is a rare find today. Happily it is available to all as a digital read right here. For Meyer's mention of the dead antelope, see pages 183-184.

***Daniel H. Johnson. Loyalty: A Biography of Richard Gustavovich Reusch (SunRay, 2008).

****See Daniel H. Johnson's notes, "Rev. Dr. Richard Gustavovich Reusch (1891-1975)." These notes are available here.