Above: Still from Rankcolor's 1990 film "Mountains of the Moon." Image found here.

View from the plane window: Magnificent. Kilimanjaro rises to meet us.

View from the ground 20 minutes later: Overcast. Clouds in every direction.

Inbound. Photo by teammember Nico Roger.

I knew Kili was up there and quite close, its hoary head peering down. But from Stella Maris (see previous post here), it was impossible to discern where the giant lay.

How do you hide a mountain? I thought. Especially the highest one in all Africa?

But of course, mountains do hide, sometimes quite successfully. And as any hiker can tell you, it is possible to even stand on a mountain and not know it is there.

Kilimanjaro excels at hide and seek, both in the present and in the past. As suggested in our post here, the earliest preserved mention of Kili may be from the hand of Claudius Ptolemy. After that 2nd century sighting, it hides again for nearly a millennium.

While defending his revision of the world map, Ptolemy's presentation wandered into East Africa and identified the birthplace of the Nile. It was west of the Rhaptum promontory in lakes filled by the melting snows of "the Mountains of the Moon" (Geography, Book 4, Chapt 8).

Ptolemy's statement sets every antenna aquiver. What were his sources? What exactly did he mean by the label "Mountains of the Moon"? By what enduring power did this label occupy the human imagination for the centuries that followed? We have far more questions than answers. Needless to say, Ptolemy's lunar range achieved iconic status. Geographers talked about it. Scholars fussed over it. Mapmakers imaginatively inked it into blank spaces. Explorers died searching for it. For a period of time, Africa's misty mountains became Geography's Holy Grail: find the lunular mountains and the Nilotic lakes would be revealed.

Image from Athanasius Kircher's 1655 map identifying the source of the Nile in a clever cut-away view of Africa. The river flows out from under the Mountains of the Moon and through Ethiopian lakes. Image from here.

Beyond Marinus of Tyre, one can only guess at Ptolemy's sources. More certain is the fact that Ptolemy lived and worked in Alexandria, Egypt. He wrote in Koine Greek and was a Roman citizen. A late (and unsubstantiated) claim by Theodore Meliteniotes in the 14th c suggests Ptolemy originally hailed from Ptolemais Hermiou, a site in Upper Egypt (about 70 miles downstream from Luxor).* Such a location would put Ptolemy up-Nile and closer to the heart of Africa and perhaps in a better position to capture rumors of travelers and traders. Still, one would imagine that information available in Luxor would have been accessible in Alexandria as well.

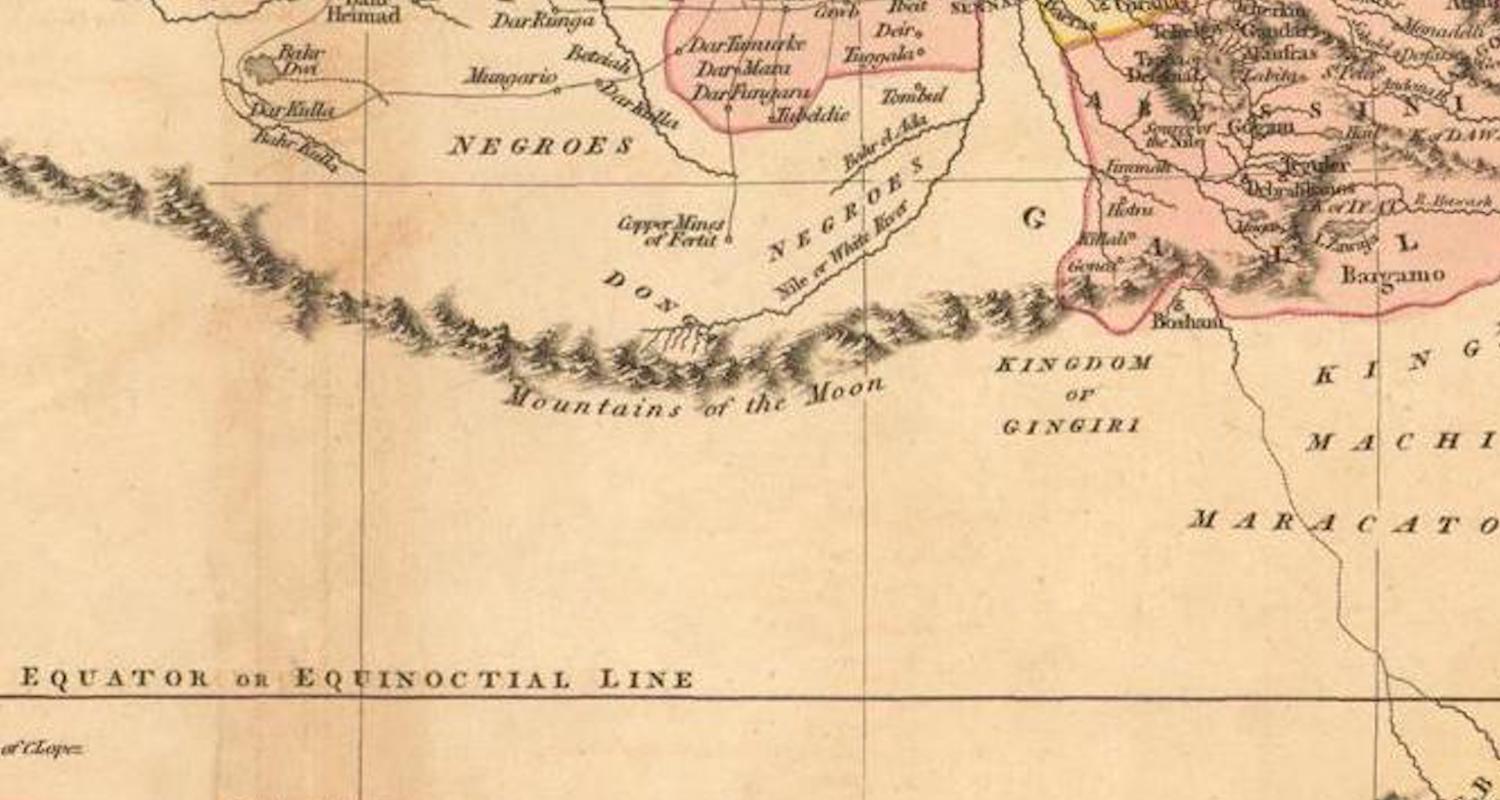

Even late in the game most of Africa was unknown to the west. In this presentation of the continent published by John Cary in 1805 the contours of the coastline are well established as are select inland areas. Note however the imaginative line of mountains that march latitudinally from Africa's eastern horn to its southwestern bulge. In the west, this range is labeled the "Mountains of Kong." In the east, they become Ptolemy's "Mountains of the Moon." South of this range are "Unknown Parts." Our source for this image is here.

Detail from the map of John Cary, A New Map of Africa (1805). Note the "Mountains of the Moon" running through the center of the image. These marked the curtain of western knowledge up to the 19th century.

Tommy, Jason, and I stand at the window on the top floor at the Stella Maris. We are armed with cameras and take pictures of where we believe the mountain to be. Below and to our left, the laundry boys splash and wring out the clothes of Stella's clients. Tomorrow morning we leave the luxuries of this hotel, I think. Early explorers had a different experience of this place.

Kili plays hide and seek with us.

The quest for Ptolemy's mountains and the Nile's lakes involved much hardship. Explorers had to deal with unforgiving geography, the complications of local populations, and, of course, a myriad of tropical maladies. One modern author claimed these mountains were aptly named; they were "lunatic" to be sure and those who sought them out would be driven mad.**

Among the first of the seekers was the Scotsman James Bruce. Bruce entered the region in the late 18th century and connected Ptolemy's lunae montes with an 8,000' formation he called the Amid-Amid (today, Mt Amidamit in Ethiopia). Bruce believed these highlands surrounded the fountain of the Nile like two semicircles. This curious shape, resembling a new moon, produced the memorable name.***

However, it was Henry ("Dr Livingstone, I presume?") Stanley who seemingly put the matter to rest. Stanley asserted that Ptolemy's "Mountains of the Moon" be associated with the 16,000' Ruwenzori range straddling the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The lakes were just below: Victoria and Nyassa. Despite the fact that the region births only a portion of the Nile and that the lakes Ptolemy described should be further south and that it is inconceivable that a 2nd century merchantman/sailor would have traveled 1,000 miles by foot into the heart of Africa (I think you are getting my drift), the identification stuck.

Catching up on my Claudius Ptolemy. It is madness, sheer madness, I tell you! Photograph by Vicki Ziese.

This majority opinion has but one competitor: Kilimanjaro. Kili's 20th c. champion was G.W.B. Huntingford, a specialist in East African cultures and languages and lecturer at the University of London. Kilimanjaro's proximity to the sea (350 miles), height, snow-cap and position line up more closely with Ptolemy's description, although the missing lakes (and river!) are complications.****

I would need to dig a little deeper in the lexicons, but might the Greek phrase commonly translated "mountains of the moon," tes selenes oros (and note that it is singular!), be translated in some other way? Perhaps it is "the silvery (bright) mountain" or even "the mountain of Selene" (as in the goddess). It is not as snazzy as "mountains of the moon" but what could Ptolemy have known of lunar landscapes anyway? This description works for any snowcap, especially an extremely high and odd one, all frosty on the equator!

I take a last photograph of what I imagine to be the base of Kilimanjaro and head downstairs. Two thousand years of ruminating has not resolved the many mysteries of Ptolemy's mountain(s). Tomorrow morning we will pull our boots on and hopefully, have a look for ourselves.

The East African explorations of Richard Francis Burton and John Hanning Speke are featured in the 1990 epic film "The Mountains of the Moon." It is well worth watching, if you can find it. " Image from here.

*See G. J. Toomer's well-supported article on Ptolemy's life here.

**For this description, see Edward Rice on Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton (HarperCollins, 1991): 355.

***Read his account in Travels to the Source of the Nile, Vol. 5, page 209. A link is found here. See also Joseph Wilson's 1810 presentation of A History of Mountains, Vol. 3, p 702.

**** See Huntingford's comments in his translation and comments on The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (Hakluyt/British Library, 1980): 174-175.

I love Africa but my regular summer work is in Israel-Palestine.

If you are a pastor, church leader, or educator who is interested in leading a trip to the lands of the Bible, let me hear from you. I partner with faith-based groups to craft and deliver academic experiences. Leaders receive the same perks that other agencies offer, at competitive prices, and without the self-serving interests that often derail pilgrim priorities.